Yes, the Fed is a drunken reckless money-printer, and the US government has been high for years on deficit spending, but other major central banks and governments do the same or worse. The long-term trends are clear, however.

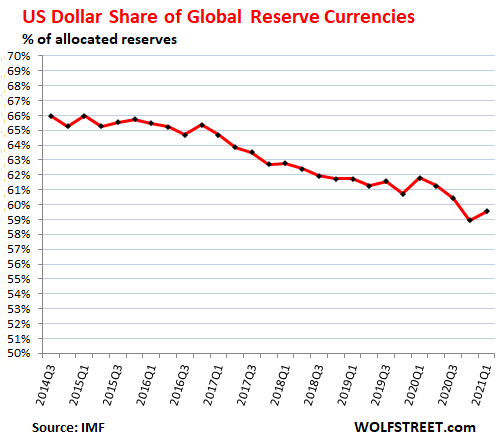

The global share of US-dollar-denominated exchange reserves ticked up to 59.5% in the first quarter of 2021, after having dropped to a 25-year low in Q4 2020, according to the IMF’s Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) data released at the end of June. Dollar-denominated foreign exchange reserves are Treasury securities, US corporate bonds, US mortgage-backed securities, US Commercial Mortgage Backed Securities, and other dollar-denominated financial assets held by foreign central banks. Q1 was a ripple in the long-term trajectory.

Since 2014, the dollar’s share has dropped 6.5 percentage points, from 66% to 59.5%, on average 1 percentage point per year. At this rate, the dollar’s share would fall below 50% over the next decade.

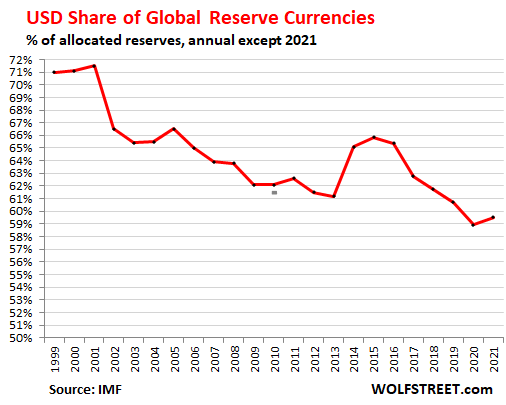

Two decades of unsteady decline

Since 1999, when the euro arrived, the dollar’s share of foreign exchange reserves has dropped 11.5 percentage points, from 71% to 59.5% (year-end shares, except Q1 2021):

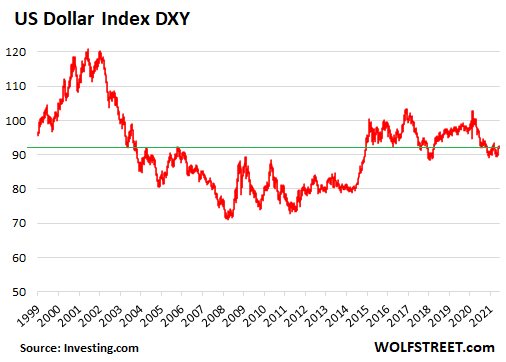

Exchange rates between the dollar and other currencies change the valuations expressed in dollars of non-dollar reserves, such as German government bonds.

Yes, but… The Dollar Index (DXY) moved substantially since 1999, up and down, but it is now roughly back where it was in 1999.

This means that nearly all of the decline in the share of the dollar as foreign exchange reserves since 1999 was due to central banks unloading dollar-denominated assets, and not due to exchange rates (data via Investing.com):

The Fed’s own holdings of dollar-denominated assets – the $5.2 trillion in Treasury securities and $2.3 trillion in mortgage-backed securities, are not included in global foreign exchange reserves.

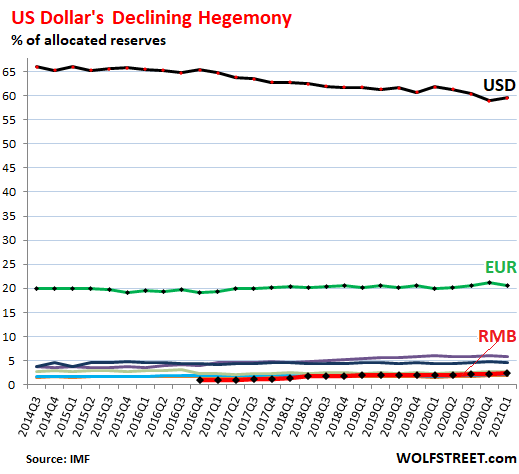

The dollar v. other reserve currencies

The euro, the second largest reserve currency, has been roughly anchored at a share of around 20% of global reserve currencies. In Q1 2021, it was at 20.5%. The ECB’s holdings of euro-denominated bonds are not included in the euro-denominated foreign exchange reserves.

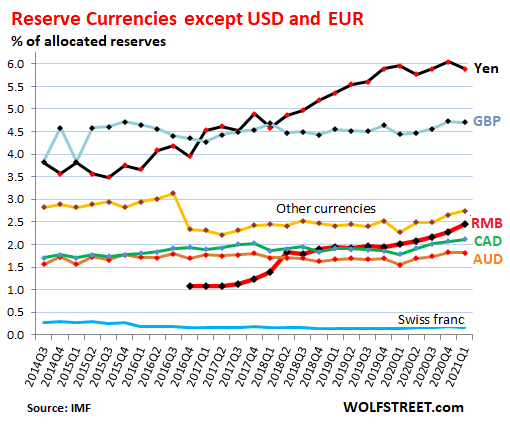

All other reserve currencies combined had a share of 19.9% in Q1. The largest ones are depicted by the colorful spaghetti bunched up at the bottom. The Chinese renminbi is the short red at the bottom:

The colorful spaghetti at the bottom

Anyone who thinks the Chinese renminbi is going to knock the dollar off its hegemonic perch needs to be very patient. The renminbi’s share of global reserve currencies is growing at snail’s pace, but it is growing.

In Q1, the renminbi reached a whopping 2.45% of total reserve currencies, though China is either the largest or second largest economy in the world, depending on how the counting is done. The renminbi is in fifth position behind the US dollar (59.5%), the euro (20.6%), the yen (5.9%), and the UK pound (4.7%), and ahead of the Canadian dollar (2.1%) and the Australian dollar (1.8%).

What this tells us is that central banks around the world are leery of the renminbi and are not eager to hold renminbi-denominated bonds, though they’re dipping their toes into them.

The chart below shows the “spaghetti at the bottom” magnified, on a scale from 0% to 6%, which cuts out the dollar and the euro. Note the surge of the yen since 2015, which outpaced the slow rise of the renminbi.

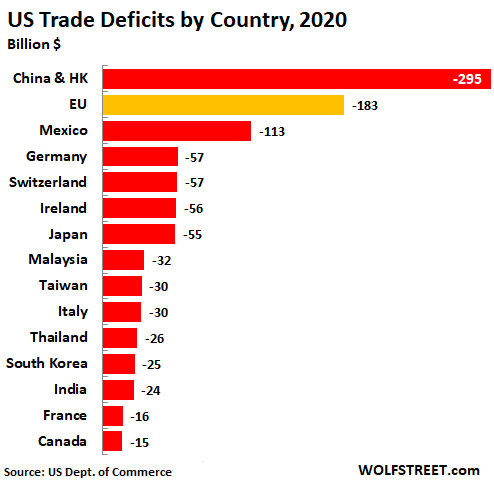

Must a country with a big reserve currency have trade deficits? Nope. But the reserve currency enables it!

The economies of the second largest reserve currency (euro), the third largest (yen), and the fifth largest (renminbi) have all trade surpluses with the rest of the world, and huge trade surpluses with the US. There is no requirement that a large reserve currency must have a large trade deficit, as it is sometimes alleged.

But having the dominant reserve currency allows the US to fund its trade deficits, and this reserve currency status thereby enables the US to have those trade deficits.

Article: The Dollar’s Declining Status as Dominant “Global Reserve Currency” v. the Dollar’s Exchange Rate