Even before the new mine became the main topic of village conversation, João Cassote, a 44-year-old livestock farmer, was thinking about making a change. Living off the land in his mountainous part of northern Portugal was a grind. Of his close childhood friends, he was the only one who hadn’t gone overseas in search of work. So, in 2017, when he heard of a British company prospecting for lithium in the region of Trás-os-Montes, Cassote called his bank and asked for a €200,000 loan. He bought a John Deere tractor, an earthmover and a portable water-storage tank.

The exploration team of the UK-based mining company Savannah Resources had spent months poring over geological maps and surveys of the hills that ripple out from Cassote’s farm. Initial calculations indicated that they could contain more than 280,000 tonnes of lithium, a silver-white alkali metal – enough for 10 years’ production. Cassote got in touch with Savannah’s local office, and the mining firm duly contracted him to supply water to their test drilling site. The return on his investment was swift. After less than 12 months on the company’s books, Cassote had made what he would usually earn in five or six years on the farm.

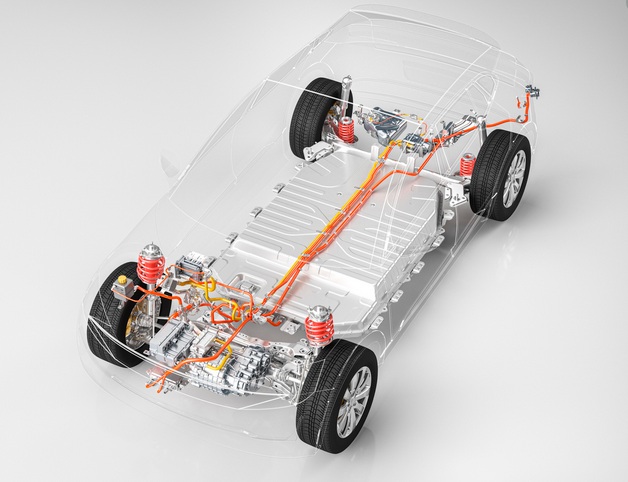

Savannah is just one of several mining companies with an eye on the rich lithium deposits of central and northern Portugal. The sudden excitement surrounding petróleo branco (“white oil”) derives from an invention rarely seen in these parts: the electric car. Lithium is a key active material in the rechargeable batteries that run electric cars. It is found in rock and clay deposits as a solid mineral, as well as dissolved in brine. It is popular with battery manufacturers because, as the least dense metal, it stores a lot of energy for its weight.

Electrifying transport has become a top priority in the move to a lower-carbon future. In Europe, car travel accounts for around 12% of all the continent’s carbon emissions. To keep in line with the Paris agreement, emissions from cars and vans will need to drop by more than a third (37.5%) by 2030. The EU has set an ambitious goal of reducing overall greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by the same date. To that end, Brussels and individual member states are pouring millions of euros into incentivising car owners to switch to electric. Some countries are going even further, proposing to ban sales of diesel and petrol vehicles in the near future (as early as 2025 in the case of Norway). If all goes to plan, European electric vehicle ownership could jump from around 2m today to 40m by 2030.

It is predicted that there will be 40m electric cars in Europe by 2030. Photograph: Ben Margot/AP

Lithium is key to this energy transition. Lithium-ion batteries are used to power electric cars, as well as to store grid-scale electricity. (They are also used in smartphones and laptops.) But Europe has a problem. At present, almost every ounce of battery-grade lithium is imported. More than half (55%) of global lithium production last year originated in just one country: Australia. Other principal suppliers, such as Chile (23%), China (10%) and Argentina (8%), are equally far-flung.

Lithium deposits have been discovered in Austria, Serbia and Finland, but it is in Portugal that Europe’s largest lithium hopes lie. The Portuguese government is preparing to offer licences for lithium mining to international companies in a bid to exploit its “white oil” reserves. Sourcing lithium in its own back yard not only offers Europe simpler logistics and lower prices, but fewer transport-related emissions. It also promises Europe security of supply – an issue given greater urgency by the coronavirus pandemic’s disruption of global trade.

Even before the pandemic, alarm was mounting about sourcing lithium. Dr Thea Riofrancos, a political economist at Providence College in Rhode Island, pointed to growing trade protectionism and the recent US-China trade spat. (And that was before the trade row between China and Australia.) Whatever worries EU policymakers might have had before the pandemic, she said, “now they must be a million times higher”.

The urgency in getting a lithium supply has unleashed a mining boom, and the race for “white oil” threatens to cause damage to the natural environment wherever it is found. But because they are helping to drive down emissions, the mining companies have EU environmental policy on their side.

“There’s a fundamental question behind all this about the model of consumption and production that we now have, which is simply not sustainable,” said Riofrancos. “Everyone having an electric vehicle means an enormous amount of mining, refining and all the polluting activities that come with it.”

In the tiny hamlet of Muro in Trás-os-Montes, Cassote has concerns of his own. The prospecting phase ended earlier this year, and his expensive new machinery is standing idle in his farmyard. Savannah is waiting for the final green light from the Portuguese government for its lithium mine. If approved, the company is promising to invest $109m in the project. It will also create a quarry like an open wound in the mountainside. Cassote doesn’t mind. He just wants to be back on his earthmover.